Abstract

ECtHR is under an obligation to account for the national constitutional values and context of the state while adjudicating on the matters relating to freedom of expression. It is generally argued by the scholars that all the cases restricting freedom of expression circumscribing public morals are subject to deference to national authorities. However, the author believes that there is a subclass within the class of public moral speeches, that are more susceptible to deference to national authorities. In this paper the author draws a distinction among the types of public moral speeches, and it will be inferred that cases of ECtHR involving sexually explicit speeches are in favour of state authorities than the general public moral cases, thereby upholding restriction on fundamental rights.[1]

Introduction to Margin of Appreciation

Constitution of every state is unique in the way it protects fundamental rights. The divergence in protection emanates from the national traditions, national constitutional values, and legal culture. As is common knowledge, for instance, the Dutch constitution emphasises the right to education;[1] Irish constitution mentions the importance of traditional family and the right to life;[2] German Grundgesetz requires human dignity as an essential principle to be respected by all public authorities.[3] These inherent differences make it difficult to reconcile with the notion of the universality of fundamental rights.[4] Since national constitutional values determine the notion of fundamental rights, the level of protection of such rights differs from state to state. In an increasingly united Europe, which is characterised by easy cross-border traffic and interaction between the States, such diverging standards of fundamental rights protection are difficult to accept. Nevertheless, they are there, and many hold on to the idea of a national constitutional identity that is reflected in national constitutional values.[5]

Within this setting, the European Court of Human Rights (“ECtHR”) is entrusted with the responsibility of developing and maintaining minimum standards of fundamental rights protection for the Council of Europe.[6] The court has to take a balanced approach rather than a maximalist approach while adjudicating on matters of any of the 46 convention states, so as to ensure that the decision is reconcilable with the unique national constitutional values and policy choices of the State involved in the dispute. In 2015, through the Brussels Declaration [7], the government leaders reaffirmed the objective of the convention and Council of Europe in the field of human rights ‘to develop the common democratic and legal space founded on respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms’. However, the declaration emphasised the ‘subsidiary nature of the supervisory mechanism established by the Convention and in particular the primary role played by national authorities and their margin of appreciation in guaranteeing and protecting human rights at the national level’. This essentially implied that the court would have to account for the national constitutional values and context of the state while adjudicating on the matters to balance the national interest vis a vis individual’s fundamental rights.

Deference to National Authorities in Cases of Public Morality

The ECtHR has played a crucial and active role in protecting the fundamental rights of individuals on issues of a diverse array of human rights. Even after accounting for the calculus of the margin of appreciation, the ECtHR has favoured individuals’ fundamental rights over national interests. For example, in cases involving freedom of expression, a right enshrined in Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, the Court has consistently found fault with how national authorities regulate freedom of speech.[8] It has determined that states violated the core right in 79% of cases it ruled on between 1961 and 2016, demonstrating its willingness to exercise its judgment even if it contradicts the findings of its members’ judicial branches.[9] However, scholars and activists have widely pointed out that cases on speech restriction under Article 10(2)[10] for the protection of morals, as a rule, encourage deference to national authorities.[11] The ECtHR has consistently maintained that a lack of uniform “conception of morals” allows for a margin of appreciation and a certain leeway for national authorities when moral claims are involved[12].This is owing to the margin of appreciation doctrine which recognises state-level variation in national traditions, national constitutional values, and legal culture, especially in cases where national courts are better placed to rule on an issue, thereby relegating the ECtHR position as a subsidiary to the national authorities. The real concern with respect to restricting freedom of speech on grounds of protection of morals stems from the fact that once ECtHR has accepted such grounds, then applying the doctrine of margin of appreciation the ECtHR is more likely to favour the national interest or the collective interest of a state over an individual’s fundamental rights.

The need for court deference to national authorities in cases of obscenity

Scholarly studies reveal that the core concern about public morals is fundamentally connected to ideas about sex. Clor,[13] in his work on obscene speech, wrote that “Laws against obscenity are often made or defended in the name of public morality”. Similarly, Nowlin[14] argued that the traditional legal philosophical analysis reflects that enforcement of morality has a distinctively sexual bearing. In his work, he draws a distinction in the sociological context as to how sexual expressions (pornography, adultery, prostitution, etc.) evoke a legal restriction on grounds of public morality while asexual expressions (tax evasion, advertising misrepresentation, etc.) do not. The relationship between morals and sex is also evident from the discussions that took place during the formation of the European Convention on Human Rights. The archives from the Council of Europe documenting the drafting of Article 10 reveal that the UN Conference on Freedom of Information submitted a draft version of Article 10(2) that had put restrictions on the expression on the grounds of “obscenity”. Subsequently, the British Government submitted a version of Article 10(2) that replaced the word obscenity with the protection of morals.[15] The substitution of words overtly made it apparent that the protection of morals phrase was introduced as a direct substitution for imposing the same or exact limitation with regard to obscene speech, thereby reflecting a strong linkage between morals and sex since the very beginning. If the insertion of the moral clause was intended to restrict sexually explicit or obscene expression, then the existing notion that the Court more often defers to national authorities on public moral cases based on textual understanding should move towards obscene speeches that deserve restriction. Although the margin-of-appreciation doctrine has been traditionally associated with public morals since the Court tends to utilize the doctrine in cases where “there is no uniform conception of morals,” this seems to apply equally well to cases with sexually explicit content. Greer[16] points out that there is more bandwidth to allow deference to states in upholding restrictions on the expression of sexuality considering the fact that a country does not become less democratic than others because it places more restrictions upon the artistic expression of certain forms of sexuality. It can be understood that the Court allows deference to states in matters of free speech. However, the author in this article examines if such deference is essentially rooted in the black letter law of the convention or if is it based on ideas about the type of speech that merits restriction. Further, it analyses to what extent Court defers to the state authorities’ decisions to restrict freedom of expression in cases involving public moral components devoid of the sexual component in comparison to those involving sexual components.

Comparative Analysis

The analysis is based on the data retrieved from the paper written by Sharma and Bleich on Freedom of Expression, Public Morality, and Sexually Explicit Speech.[17] They categorised the primary dataset into two parts – Public Morality Cases and Sexually Explicit Speech Cases. Public morality cases were defined as those in which the Court upholds the restriction on the expression on grounds of public morals as a legitimate aim. Whereas sexually explicit speech encompasses all those cases in which the Court’s rationale is similar to that in an obscenity case, but the speech acts themselves are not extreme enough to be considered obscenity. For identifying cases on Public Morality, the author retrieved cases from the HUDOC database using the search term “Article 10(2) – Protection of Morals ”. Thereafter, twelve judgments were identified from the larger database that were substantially decided on the grounds of morality under Article 10 (2). On the other hand, the cases of sexually explicit speech were identified using search terms “Article 10” and “obscene” or “naked” or “sexual” or “pornographic”, etc. From the preliminary data of 121 cases, only ten relevant cases constituted part of the core data. This was owing to the fact that over 90% of the cases were on reports on the torture of prisoners, newspaper articles containing allegations of sexual assault, and scandals involving illicit sexual relations. Therefore, these 90% of cases which formed the part of the preliminary dataset were removed from the core dataset to essentially target cases on sexually explicit speech as defined earlier. The entire sample space of Public Morality and Sexually Explicit Speech was reduced to 16 cases and further categorised under three categories –

a. Only Sexually Explicit Speeches

b. Intersection of Sexually Explicit Speeches and Public Morality

c. Only Public Moral Cases.

The following table of the summary will reflect that 5 out of 6 cases on Public Morals only were found to be in violation of Article 10, thereby upholding an individual’s fundamental right. However, 4 out of 6 and 3 out of 4 cases were found not in violation of Article 10 when the matter concerned was at intersection and Sexually Explicit Speech only respectively, thereby upholding restriction on the fundamental right in the interest of the state.

| Table of Cases[18] | |||

| Year | Cases | Outcome (Article 10) | |

| Public Morals Only | |||

| 1992 | Open Door and Dublin Well Woman v. Ireland | Violation | |

| 2003 | Gunduz v. Turkey | Violation | |

| 2006 | Erbakan v. Turkey | Violation | |

| 2006 | Aydin Tatlav v. Turkey | Violation | |

| 2018 | Sinkova v. Ukraine | No Violation | |

| 2018 | Sekmadiienis Ltd v. Lithuania | Violation | |

| Intersection | |||

| 1976 | Handyside v. UK | No Violation | |

| 1988 | Muller and Others v. Switzerland | No Violation | |

| 2005 | I.A. v. Turkey | No Violation | |

| 2010 | Akdas v. Turkey | Violation | |

| 2012 | Mouvement raelien Suisse v. Switzerland | No Violation | |

| 2016 | Kaos GL v. Turkey | Violation | |

| Sexually Explicit Speech Only | |||

| 1994 | Otto Preminger Institut v. Austria | No Violation | |

| 1996 | Wingrove v. UK | No Violation | |

| 2007 | Vereinigung Bildender Kunstler v. Austria | Violation | |

| 2011 | Palomo Sanchez and Others v. Spain | No Violation | |

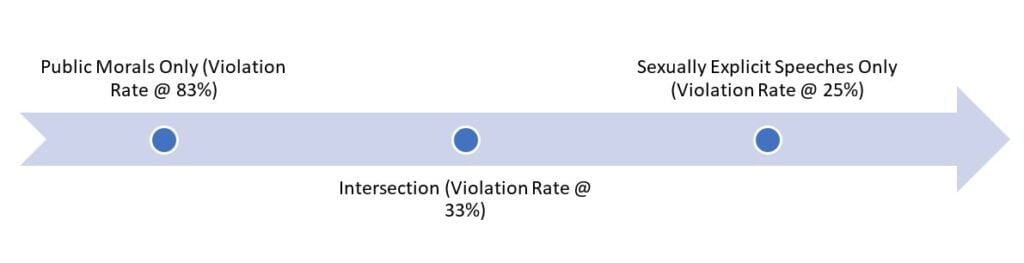

If we look at this model where Public Moral Cases are at one end of the spectrum and Sexually Explicit Speech is at another end and in between lies the intersection of the two. It can be inferred that the court upholds restrictions on fundamental rights in cases as we move across the spectrum from left to right, thereby showing more deference to national authorities in cases of Sexually Explicit Speeches than on Public Morals alone. It can also be inferred from the downward trend in Violation Rate[19] that in cases involving Public Morality, the Court upholds the protection of an individual’s fundamental rights as opposed to cases involving Sexually Explicit Speeches where the Court as a rule upholds restrictions on fundamental rights imposed by the state.

Case Analysis Across Spectrum

Cases Involving Public Morals Only

The general scholarly conception that the Court deferred to national authorities in all public moral cases is a skeptical observation. Apparently, the data suggests that Sinkova v. Ukraine[20] was the only case out of many in which the court favoured the national authority. Inference of no violation by the Court in public morals-only cases is rather an exception to the rule. Open Door and Dublin Well Woman v. Ireland[21] and Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania[22] exemplify this point.

In Open Door, the Irish government-imposed restriction on counselling clinics that provided consulting services to pregnant women regarding obtaining an abortion from abroad. This restriction was primarily imposed on the grounds of the protection of morals. The state contended that abortion was morally wrong and such belief is held by the majority of people in Ireland, therefore the Court should not impose a viewpoint in contravention of the state authority. However, ECtHR ruled against the state concluding that the actions were not proportionate to the aims pursued as the laws in Ireland did not put a ban on citizens travelling abroad and obtaining an abortion. Essentially, this decision was on an extremely sensitive issue surrounding religious sentiments for a country deeply entrenched in religion but the court still ruled against it. In Sekmadienis, the court again ruled against the state and criticised the rationale being neither relevant nor sufficient for restricting freedom of expression. The state had contended that the use of models resembling Jesus and Mary in the advertisement by the appellant were contrary to public moral as they had used them for superficial purposes and inappropriately, therefore the restriction was justified. The court ruled in favour of the appellant stating that the state took a maximalist approach in protecting the sentiments of the majority without balancing the right of freedom of expression of the appellant.

Sinkova v. Ukraine[23] was the only exception where the court ruled in favour of the state. The facts of the case were set in an environment that demanded the conviction of the appellant. The appellant happened to have been fined by the state for recording a video of herself frying an egg over the Eternal Flame at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the Eternal Glory Memorial in Kyiv. The court ruled in favour of the state concluding that the applicant was not convicted for expressing the act in the video but her conviction was with respect to a particular conduct in a specific setting.

The analysis of these cases allows us to infer that a moral clause per se cannot act as a trump card for the states to obtain a ruling in their favour.

Cases Involving Sexually Explicit Speeches Only

The cases of Otto-Preminger-Institut v. Austria[24] and Wingrove v. the United Kingdom[25] exemplify the fact that the Court generally defers to the stance of state authorities in cases involving sexually explicit speech exclusively. In both these cases, the government had imposed restrictions/bans on showing the video or film as it was considered blasphemous and obscene. In Wingrove, a short film called Visions of Ecstasy portrayed St Teresa and Jesus in a sexually explicit manner inciting sexual arousal. While in the case of Otto, a film involved scenes of erotic tension between the Virgin Mary and the devil and other scenes that include the Virgin Mary Permitting an obscene story to be read to her. In both these cases, the court held that respect for the religious feelings of believers can move a state legitimately to restrict the publication of provocative portrayals of objects of religious veneration.[26] The sexually explicit components in the speeches were essentially shaking the religious sentiments of the majority, and it is that explicitness and obscenity that motivated the court to favour the state.

Vereinigung Bildeder Kunstler v. Austria[27] is the only case in the data set where the court found an Article 10 violation. This case involved paintings depicting several well-known public figures in sexual positions. The court ruled in favour of the individual as the painting constituted satire a highly protected form of speech. Ironically in the case of Palomo Sanchez and Others v. Spain[28], the court ruled in favour of the state in yet another case that involved satire and sexually explicit speech. In this case, the employees of the trade union had published a sexually explicit satirical cartoon that insulted the human resource manager of the company. The court drew a distinction between the Vereinigung case and the Palomo case and was of the opinion that private individuals enjoy greater fundamental rights protection than the public figures portrayed in Vereinigung. This decision happens to be a fairly contentious decision and an exception to the established trend. However, generally, the trend in sexually explicit speech is to leave the matter in the hands of national authorities.

Cases Involving Intersection of Public Moral and Sexually Explicit

In cases involving the intersection of sexually explicit speech and public moral cases, the trend is generally similar to that of sexually explicit speeches. Thereby concurring with the fact that the sexual component of the speech. Out of the six cases in the data set, the author will examine only two cases where the court found the state’s act in violation of Article 10.

In the case of Akdas v. Turkey[29], the Court concluded that the ban imposed by the state on the publication of a translation of Guillaume Apollinaire’s Les 11000 Verges was in violation of Article 10 because the erotic novel had first appeared in 1907 and had become part of the European literary heritage. Similarly, in Kaos GL v. Turkey (2016)[30], a case involving pornographic content expressed in a magazine by Kaos GL, a research association for LGBT, the Court essentially concluded that had the government decided to restrict access to the material in order to protect minors, it would have been an acceptable action, but the decision to ban the material entirely was disproportionate to the narrower aim of protecting minors and violated Article 10(2). In both of these cases, the court observed that violations were based on factual circumstances rather than on the question of law examining the nature of speech. Therefore, it can be concluded from the other four cases where no violation was observed that the Court generally acts in favour of the state in cases of public morality involving a sexual nature of the speech. In the cases of Handyside[31] and Muller[32], where the Court upheld the restriction, and held that sexual speech become a decisive factor in determining morality, thereby allowing the national authorities a larger discretion in such cases. This suggests that apart from a few exceptions the government’s claim invoking the public moral clause is more likely to succeed in its favour when the case involves a sexual component than the public moral cases not involving a sexual component. This is essential because the nature of speech itself forms the basis of restriction.

Conclusion

The author has analysed the restriction imposed on speeches by invoking the protection of the moral clause under Article 10(2) of the ECtHR. It is proved through analysis of several landmark cases across the last three decades, that it is the nature of the speech that trumps over the black letter law of the Convention to decide when the Court more likely defers to the national authorities. The general scholarly conception that the Court defers to national authorities in most of the cases where the moral clause is invoked was proved to be deviant to our analysis. Rather, our study suggests that in cases involving sexual components in public moral cases, the court is more likely to defer to national authorities and uphold restrictions than in cases exclusively concerned with public morals devoid of sexual components.

This article is a part of the DNLU-SLJ (Online) series, for submissions click here.

Download the Pdf version of this article.

[1] Article 23 of the Dutch Constitution (Grondwet).

[2] Article 40.3.3 of the Constitution of Ireland.

[3] Article 1 of the German Basic Law (Grundgesetz).

[4] Janneke Gerards, Margin of Appreciation and Incrementalism in the Case Law of the European Court of Human Rights, Human Rights Law Review, Volume 18, Issue 3, September 2018, Pages 495–515, https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngy017

[5] Cloots E, National Identity and the European Court of Justice (PhD thesis, University of Leuven, 2013).

[6] McGoldrick D, “A Defence of the Margin of Appreciation and an Argument for Its Application by the Human Rights Committee” (2015) 65 International and Comparative Law Quarterly 21.

[7] Brussels Declaration, “Implementation of the European Convention on Human Rights, our shared responsibility” https://www.echr.coe.int/documents/brussels_declaration_eng.pdf.

[8] Chicowski R and Chrun E, “The European Court of Human Rights Database”. http://depts.washington.edu/echrdb/.; Keck T, “Assessing Judicial Empowerment” (2018) 7 Laws 14 http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/laws7020014.

[9] Ibid 8.

[10] Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

[11] Cora Feingold, “The Doctrine of Margin of Appreciation and the European Convention on

Human Rights” (1977) 53 Notre Dame Law Review. George Letsas, “Two Concepts of the Margin of Appreciation”, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, Volume 26, Issue 4, Winter 2006, Pages 705–732, https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/gql030.

[13] Randall RS, “Obscenity and Public Morality; Censorship in a Liberal Society By Harry M. Clor. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1969. Pp. 315)” (1969) 63 American Political Science Review 1289 http://dx.doi.org/10 (2)307/1955092.

[14] Nowlin CJ, “The Protection of Morals under the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms” (2002) 24 Human Rights Quarterly 264.

[15] Neha Sharma & Erik Bleich, ‘Freedom of Expression, Public Morals, and Sexually Explicit Speech in the European Court of Human Rights’ (2019) 5 Const Stud 55.

[16] Steven Greer, “The Exceptions to Article 8 to 11 of the European Convention on

Human Rights.” (Strasbourg: Council of Europe 1997).

[17] Ibid 16.

[18] Ibid 14.

[19] Violation Rate essentially reflects the percentage of cases in which the Court has acknowledged violation of Article 10 by the state, therefore not deferring to the national authority and upholding the individuals fundamental right as opposed to the national interest of the state.

[20] Sinkova v. Ukraine App no. 39496/11, (ECHR, 7 February 2018).

[21] Open Door in Dublin Well Woman v. Ireland App no 14234/88, (ECHR, 5 March 1992).

[22] Sekmadienis Ltd. v. Lithuania App no 69317/14, (ECHR, 30 April 2018).

[23] Ibid 17.

[24] Otto-Preminger-Institut v. Austria App no 13470/87, (ECHR, 20 September 1994).

[25] Wingrove v. the United Kingdom App no 17419/90, (ECHR, 25 November 1996).

[26] Ibid 21; Ibid 22.

[27] Vereinigung Bildeder Künstler v. Austria App no 68354/01, (ECHR, 5 April 2007).

[28] Palomo Sanchez and Ohen v. Spain App no 28955/06, 28957/06, 28959/06, and 28964/06, (ECHR, 12 September 2011).

[29] Akdas v. Turkey App no 41056/04, (ECHR, 16 February 2010).

[30] Kaos GL v. Turkey App no 4982/07, (ECHR, 22 November 2016).

[31] Handyside v. UK App no 5493/72, (ECHR, 7 December 1976).

[32] Muller and Others v. Switzerland App no 10737/84 (ECHR, 24 May 1988).

Student at Jindal Global Law School, O.P. Jindal Global University Sonipat